Feds flag human services grants shakeup

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

The federal government is trialling longer-term contracts for not-for-profits that deliver…

Posted on 01 Sep 2025

By Jen Riley, chief impact office, SmartyGrants, and Dr Liz Branigan, knowledge and practice director, Philanthropy Australia

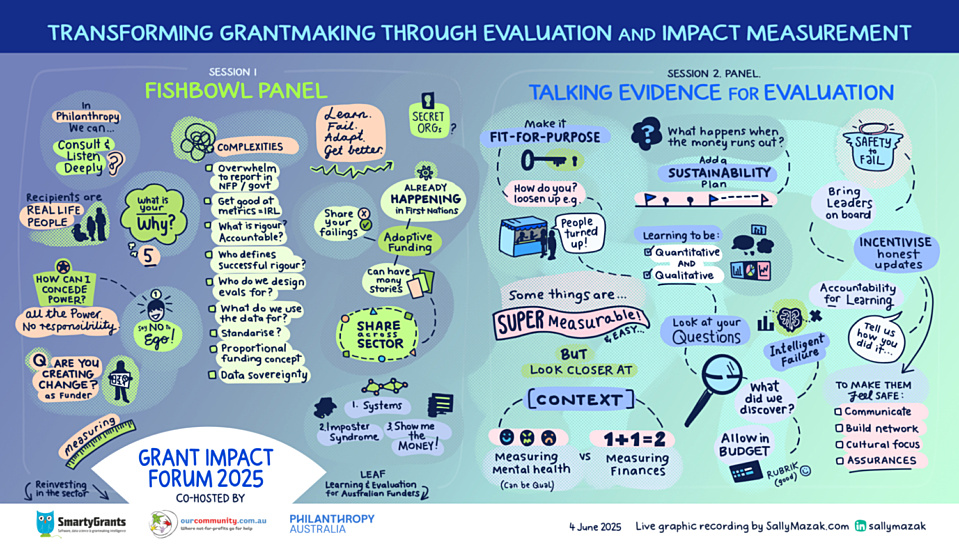

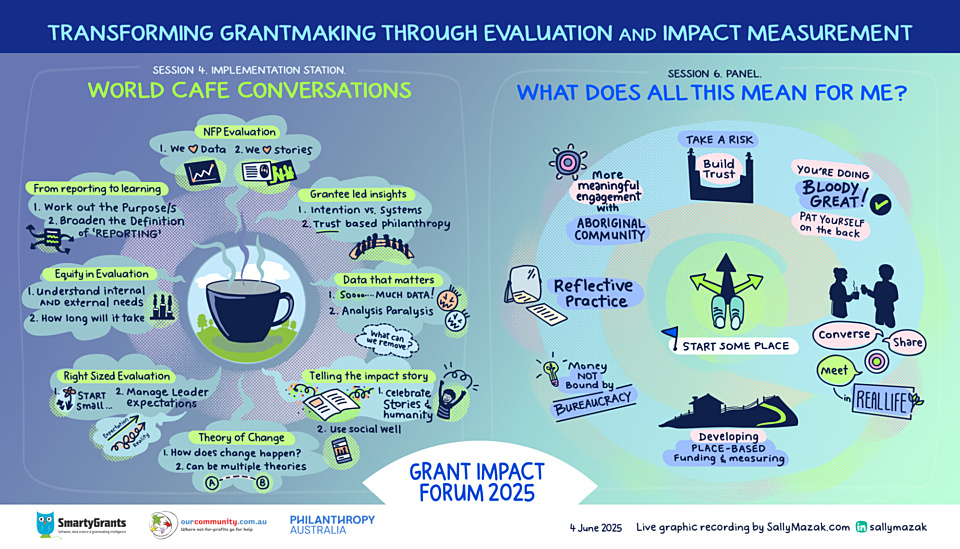

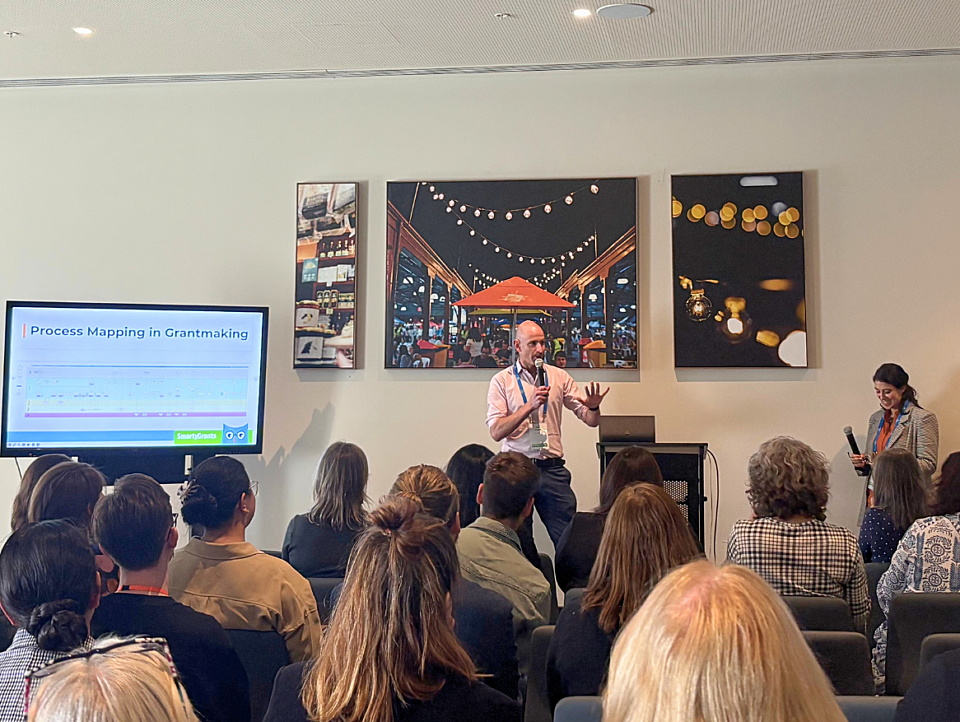

The Grant Impact Forum held in Melbourne in June didn’t begin with a keynote or a panel.

Instead, the all-day event began with a “fishbowl” conversation – a

participatory format centred on four chairs. Any of the 80 attendees could step

in, occupy a chair, speak, and step back out. The format was designed to

flatten hierarchies, build trust, and encourage diverse views. And it did.

As people spoke, the fishbowl became more than a format. It mirrored the current state of grant evaluation – at times clear, at times confusing; often valuable, but full of tension. And it raised a fundamental question:

The forum brought together funders, grantmakers, evaluators, community leaders and sector partners to focus on understanding, measuring and improving the impact of grants. “What are we really doing here?” wasn’t a cynical question – it reflected care and concern. It came from people who believe in this work but sense that something isn’t aligned. Here’s what emerged.

“Sometimes we make this way too complex. We need to swing back to what is realistic, and to understanding our why.”

The discussion quickly turned to power – particularly, who gets to define success and what counts as evidence.

Jeremy Motbey, grants and impact manager at Ecstra Foundation, put it plainly: “As a philanthropist, you have all the power and none of the responsibility… You define what success is. How do I break down that power?”

It struck a chord. Many in the room recognised the imbalance – in setting outcomes, choosing methods and interpreting results.

Dr Jess Dart, founder and CEO of Clear Horizon Consulting, added, “Rigour isn’t just about method. It’s about how we show up, how we’re aware of power, how we sit with other worldviews, how we listen.”

Impact evaluation, the group agreed, is not neutral. It is an act of meaning-making – and, if not approached carefully, an exercise in power that validates some perspectives while excluding others.

Skye Trudgett, CEO of Kowa and a First Nations evaluation leader, said, “Impact measurement and evaluation is already happening in many communities, but it might not look like what funders expect.”

The challenge was clear: if funders define success based only on external perspectives, they risk missing what’s working.

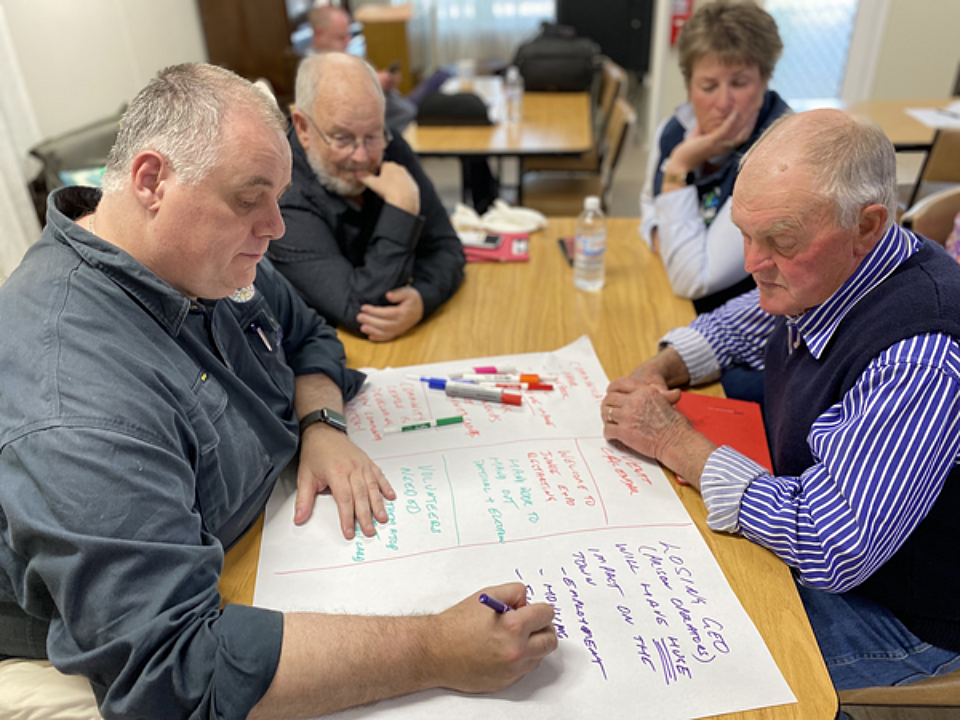

The conversation shifted to capability. Many participants – especially those from smaller organisations – spoke of feeling overwhelmed by evaluation expectations.

Monique O’Keeffe, from the City of Greater Dandenong, said, “It feels overwhelming to even look at the idea of what is an outcome, what is a metric… If you’re a volunteer organisation, you might not even understand what’s involved.”

Kate Randall, from the Community Broadcasting Foundation, raised the issue of proportionality: “A $6,000 grant to a local group versus a multi-million-dollar grant to a peak body – what we can ask of them in terms of evaluation is completely different.”

Cynthia Scherer from the Anthony Costa Foundation captured it well: “Sometimes we make this way too complex. We need to swing back to what is realistic, and to understanding our why.”

Evaluation, the group agreed, must be right-sized – matched to context, capacity and purpose.

The group then turned to systems-level evaluation. There was interest in moving beyond project outcomes to assessing broader change – but there was also caution.

One speaker warned, “It’s easy to say you’re evaluating systems change. But if you do it poorly and leave out critical variables, there are real-world human impacts.”

The example of the Department of Social Services’ payment by outcomes trial was salient. Because of rigid outcome criteria, some children – including those with disabilities and from asylum seeker backgrounds – were unintentionally excluded.

The trial showed how evaluation design can cause harm when it lacks inclusivity and care.

The lesson: changing evaluation frameworks without fully considering who might be excluded can replicate – or worsen – existing inequalities.

A powerful contribution came from Trudgett, who reminded participants that evaluation is already occurring in many Indigenous communities – just not always in ways funders recognise.

“Communities are already doing evaluation, through conversation, sense-making, relationship. Our job is to recognise and respect that.”

She also challenged funders to reflect on their role: “Funders should ask: how are we turning up? Are we creating change, or asking the community to validate us?”

And she had this message for funders: “Don’t talk out both sides of your mouth”, a sharp reminder not to say one thing ( “we’re flexible, trust-based, community-led”) while doing another (requiring burdensome reporting, providing rigid funding terms). Stated values and actual practices must be aligned, especially in power-imbalanced contexts like funding.

Respecting Indigenous knowledge and upholding data sovereignty are not optional, she said. They are essential to ethical evaluation.

One question posed during the session was “How many of you, when a program wasn’t going well, were able to approach your funder and have them respond with benevolence, time, and extra cash?”

Only one person raised their hand. That person, not-for-profit leader Thea Stinear, shared her experience: “We had the biggest screw-up… I went to the funder and said, it’s gone badly. He said, here’s more money, write up your learnings, share them with the sector. That was one of the most meaningful grants we ever had.”

The story underscored the power of learning-oriented relationships. For evaluation to enable learning, funders must be willing to respond with trust, flexibility and resources.

The conversation also turned to data – and its potential both to provide insights and to cause harm.

Squirrel Main, formerly evaluation manager at the Paul Ramsay Foundation and the Ian Potter Foundation, said several US philanthropic organisations were now deleting all evaluation data they’ve collected, fearing it could be misused by future governments.

This prompted a strong response from Trudgett: “This raises fundamental questions about data sovereignty, not just for First Nations communities, but for everyone.”

The issue isn’t just privacy. It concerns ownership, consent and long-term consequences. Evaluation must be methodologically sound and ethically safe.

A core theme of the fishbowl session was that evaluation is not just technical – it is relational.

“How we show up, how we listen, how we relate – this is rigour,” Dart said

Trudgett echoed her: “Communities are already doing evaluation, through conversation, sense-making, relationship.”

This is not just sentiment – it reflects a shift in mindset. Evaluation should be a process of engagement, not just measurement.

What if our role is not to validate someone else’s story, but to walk alongside it?

The fishbowl conversations reinforced the idea that evaluation is not neutral. It is embedded in relationships of power, trust and accountability. Done well, it can support learning, equity and progress. Done poorly, it can reinforce control.

Participants didn’t claim to have all the answers. But the forum revealed and shaped shared beliefs – among them, that meaningful evaluation requires us to:

These are not small asks. But they are necessary if we want evaluation to serve as a tool for improvement – not oversight.

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

The federal government is trialling longer-term contracts for not-for-profits that deliver…

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

A Queensland audit has made a string of critical findings about the handling of grants in a $330…

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

The federal government’s recent reforms to the Commonwealth procurement rules (CPRs) mark a pivotal…

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

With billions of dollars at stake – including vast sums being allocated by governments –grantmakers…

Posted on 15 Dec 2025

Nearly 100 grantmakers converged on Melbourne recently to address the big issues facing the…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

Just one-in-four not-for-profits feels financially sustainable, according to a new survey by the…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

The Foundation for Rural & Regional Renewal (FRRR) has released a new free data tool to offer…

Posted on 10 Dec 2025

A major new report says a cohesive, national, all-governments strategy is required to ensure better…

Posted on 08 Dec 2025

A pioneering welfare effort that helps solo mums into self-employment, a First Nations-led impact…

Posted on 24 Nov 2025

The deployment of third-party grant assessors can reduce the risks to funders of corruption,…

Posted on 21 Oct 2025

An artificial intelligence tool to help not-for-profits and charities craft stronger grant…

Posted on 21 Oct 2025

Artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming an essential tool for not-for-profits seeking to win…